Focal lymphocyte infiltration in thyroid tissue. Thyroglobulin autoantibodies (TgAA) can be detected in laboratory samples.

What is canine hypothyroidism?

Hypothyroidism is one of the most common endocrine diseases in dogs, with estimations suggesting that approximately 0.2 – 0.6% of the canine population are affected (Tappin, 2015). Disease usually develops insidiously over months to years, and is typically seen in middle aged dogs.

What causes canine hypothyroidism?

The pathogenesis of primary canine hypothyroidism is well documented in the veterinary literature. Two main forms exist, lymphocytic (autoimmune) thyroiditis and idiopathic atrophy (Graham et al 2007).

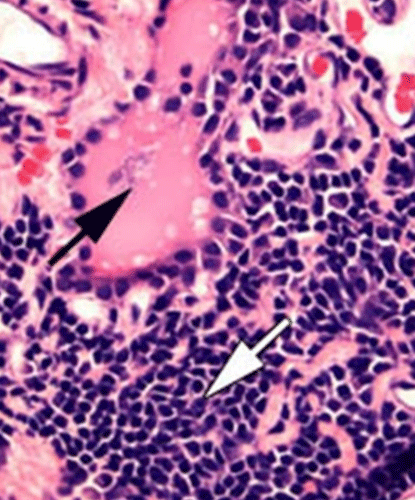

Lymphocytic Thyroiditis

Lymphocytic thyroiditis is the most common form of primary hypothyroidism in canine species. It is believed that it is an autoimmune disease which, through an inflammatory process, leads to the destruction of thyroid follicles and eventually to their replacement with connective tissue (see black arrow).

The course of disease is slowly progressing and it can take months to years for more than 75% of the thyroid tissue to be destroyed and clinical symptoms to appear.

Histologically, the disease is characterised by diffuse, multifocal infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages (see white arrow). In parallel, autoantibodies against thyroid antigens such as thyroglobulin, T4 and T3 can be detectable in the blood.

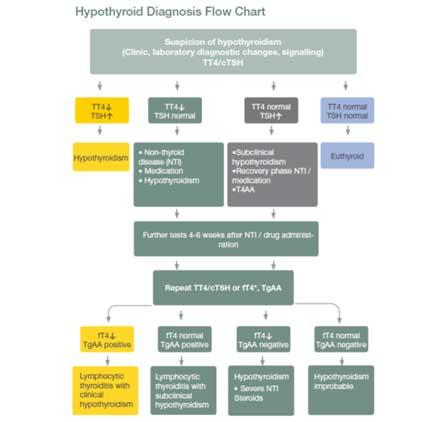

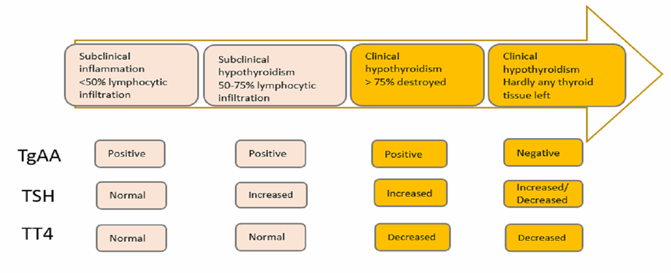

In the development of hypothyroidism due to lymphocytic thyroiditis, there are four stages (Mooney and Shiel, 2012). The list below details the characteristics of each stage:

1) Subclinical (silent) thyroiditis: add

2) Subclinical hypothyroidism: add

TgAA and an increase in thyroid-stimulating hormone (cTSH) laboratory diagnostically detectable. Total T4 (TT4) concentration still in the reference range (due to increased cTSH stimulation).

3) Clinical hypothyroidism: add

The inflammation has destroyed almost all the thyroid tissue and the TT4 concentration can no longer be maintained. TSH increases and clinical signs of disease start to appear.

4) The non-inflammatory, atrophic hypothyroidism: add

Inflammatory cells withdraw. Thyroid tissue is replaced by fibrotic tissue and fat. TgAA no longer detectable, and cTSH concentration can decrease (presumably due to exhaustion of the pituitary cells).

Idiopathic thyroid atrophy

In most dogs with non-inflammatory hypothyroidism, idiopathic thyroid atrophy is noted. This is characterised by a degeneration of the follicular cells and their replacement by connective and adipose tissue.

The cause is not known. It may be an independent degenerative disease of the follicular cells. It is debated whether, in a part of the cases, it is the last stage of lymphocytic thyroiditis.

Autoantibodies against thyroid glands cannot be (or are no longer) detected.

Other, very rare, causes of primary hypothyroidism are:

- Neoplastic destruction of the thyroid gland

- Anti-thyroid medication

- Radiation therapy

- Congenital primary hypothyroidism (cretinism)

In less than 5% of cases, there is secondary atrophy of thyroid follicles due to a TSH deficiency (secondary hypothyroidism). The causes of this can be trauma, malformations, operations or tumours of the pituitary gland.

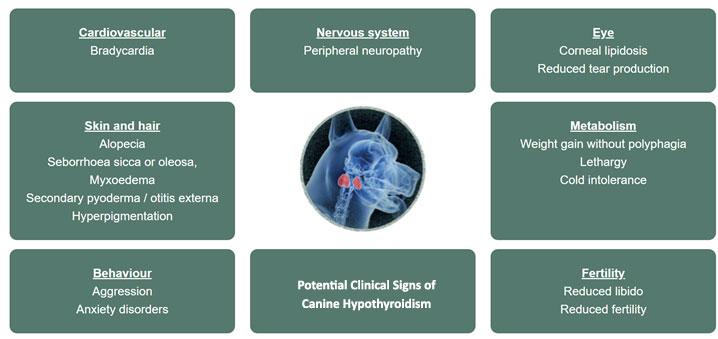

What are the clinical signs of hypothyroidism in dogs?

Symptoms associated with hypothyroidism manifest only when 75% of the thyroid tissue has been destroyed. The thyroid hormones play an important role in carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism. In addition, they influence the heat balance and oxygen consumption of many tissues. On the heart they have a positive inotropic and chronotropic effect. Therefore, the symptoms are very diverse and often initially give only vague indications of hypothyroidism.

Clinically, hypothyroidism can present in many ways, including cardiovascular, neurological, dermatological and metabolic symptoms:

Changes in metabolism

Metabolic signs of hypothyroidism include apathy, lethargy, weakness and weight gain despite normal or even reduced appetite.

Lethargy occurs in up to 80% of cases. The duration of the disease seems to correspond to the severity of lethargy (cases are reported where dogs fall asleep during the consultation).

add

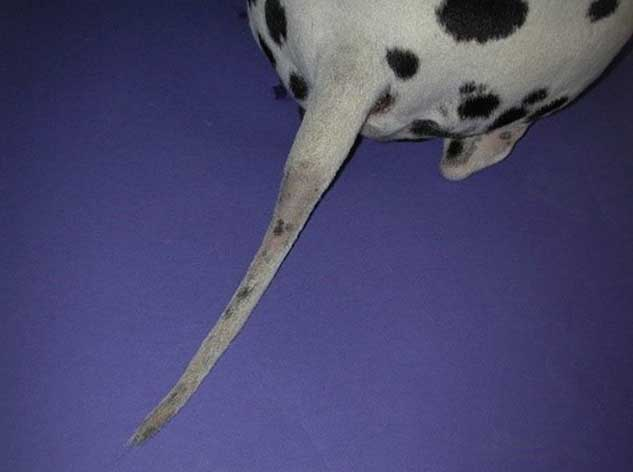

The most common symptoms of hypothyroidism include skin and haircoat changes.

Alopecia is recognised as a common sign associated with hypothyroidism. The thyroid hormones are necessary for the initiation of the anagen phase of hair growth. In the case of a thyroid hormone deficiency, the hair remains in the telogen phase and becomes easily epilated.

Alopecia usually begins in areas where pressure and friction of the haircoat occurs, e.g. on the neck (where the collar is attached), on the nose or on the tail (so-called "rat tail"). In more severe cases it can develop to a full endocrine (bilaterally symmetric) alopecia.

Skin infections secondary to hypothyroidism are also clinically seen. The thyroid hormones are involved in the immune response. Recurrent pyoderma or otitis externa often occur (10-20% of cases of hypothyroidism).

add

Another typical dermatological symptom of hypothyroidism is myxoedema.

This occurs due to a build-up of mucopolysaccharide and hyaluronic acid in the skin, so that it becomes thicker. This can be seen most clearly on the head. The thickening of the lips and the hanging of the eyelids (due to the thickened forehead skin) can lead to a sad or tragic facial expression.

How do I reach a diagnosis of canine hypothyroidism?

After analysis of history and clinical signs, routine haematology and blood biochemistry is usually taken to determine non-specific indicators of hypothyroidism. These include:

- Normochromic, normocytic, non-regenerative anaemia (mild)

- Hypercholesterolemia (mild to high grade, increases of 6 to 8 times the upper reference value limit possible)

- Hypertriglyceridemia (mild to high grade)

- Increased fructosamine concentration (mild)

- ALT, ALP elevations (mild)

For a definite diagnosis, prior to commencing therapy, the thyroid hormone thyroxine (total T4, TT4) is usually determined in conjunction with the cTSH. In addition, it is possible to determine the free, not bound to protein T4 (fT4) by equilibrium dialysis or TgAA, or less often against T4 or T3

The FAQs below answer common questions posed on each of the thyroid specific biochemical markers:

What are the advantages and disadvantages to measuring serum total T4 (TT4) when diagnosing canine hypothyroidism? add

When clarifying hypothyroidism, the determination of the TT4 value is usually the first step. In the geriatric blood chemistry profiles, TT4 is often routinely included. The measurement is simple and relatively inexpensive.

Over 95% of hypothyroid dogs have a low TT4, i.e. the sensitivity of the test is very high. However, it is problematic that the TT4 is influenced by many factors (see "Influences on thyroid hormones"). The specificity is relatively low.

Therefore, a low TT4 measurement alone is not sufficient to diagnose hypothyroidism. However, a normal TT4 concentration practically excludes hypothyroidism.

On the one hand, it could be a very early phase of hypothyroidism, in which the TT4 is still in the low-normal reference range. However, it is then questionable whether in this phase the observed symptoms, such as poor performance, are already due to the hypothyroidism. In this case, it makes sense to wait and retest. Hypothyroidism is a progressive disease and a change in blood values (further decreases in TT4) are to be expected over time.

If thyroid autoantibodies are present against thyroid hormones or thyroglobulin, these can lead to the fact that the TT4 is measured normally or even increased by in vitro interference. One way out of the situation in such cases is to determine fT4.

When / why should I measure free thyroxine (fT4) as part of the diagnosis for canine hypothyroidism? add

fT4 is the biologically active thyroid hormone and accounts for only 0.1% of TT4.

Although fT4 levels are less affected by drugs and non-thyroid diseases, low fT4 concentrations can also occur without hypothyroidism. Conversely, dogs with hypothyroidism can also have normal fT4 values. The sensitivity of a low fT4 is between 80 and 98%, the specificity is about 93%.

The main indication for determining fT4 in dogs should be in those animals where there is a suspicion of the presence of thyroid autoantibodies. In contrast to the measurement of the TT4, that of the fT4 is not influenced by the autoantibodies, provided that the measurement was measured following dialysis.

Why is it important to determine the method through which a laboratory measure free thyroxine? add

Measurement method has an important influence on the sensitivity and specificity of free thyroxine for diagnosing hypothyroidism in dogs.

Very good results are obtained by using equilibrium dialysis. The fT4 is separated from the protein-bound T4 by a dialysis membrane and then the fT4 is measured in the dialysate with an ultrasensitive radioimmunoassay. Since this process is relatively complex and expensive, it is only offered by a few laboratories and usually only carried out on special request.

In most laboratories, fT4 is routinely declared through the use of analogue methods that originate from human medicine and have therefore been optimised for humans. Therefore, the use of such tests in dogs leads to a very poor sensitivity and / or specificity.

Should I measure total triiodothyronine (TT3) when diagnosing hypothyroidism in dogs? add

The determination of T3 for diagnostic confirmation is not useful.

What are the advantages and disadvantages to measuring canine thyroid stimulating hormone (cTSH) when diagnosing canine hypothyroidism? add

Due to the pituitary-thyroid axis, an increased cTSH is to be expected with a hypothyroid metabolic situation. However, unlike humans, the determination of cTSH in dogs is not a good screening test (sensitivity: 63-87%).

For the lack of increase in cTSH concentration in hypothyroid dogs, there are several explanations:

- Occurrence of different cTSH isomers with different glycosylation patterns that are not detected by the TSH test

- Depletion of the pituitary gland (cTSH producing cells) with a longer hypothyroid state

- Proportion of dogs with secondary hypothyroidism (pituitary problem) greater than previously thought

- Simultaneously present non-thyroid disease

- Physiological fluctuations

The specificity of an increased cTSH concentration is between 82 and 98% and is therefore relatively high.

There are only a few exceptions that lead to a false positive cTSH value without the presence of hypothyroidism:

- Sulphonamide treatment

- Recovery period of a non-thyroid disease

- After discontinuation of experimental therapy with thyroxine

- During trilostane therapy in dogs with Cushing's syndrome

- In dogs with newly diagnosed hypoadrenocorticism (Addison's disease) before the start of glucocorticoid therapy

In dogs with hypoadrenocorticism, cTSH may be so greatly increased before the start of prednisolone therapy that it may be in the area of a dog with hypothyroidism. If both diseases come into question on the basis of the symptoms, e.g. lack of performance, it is advisable to first exclude and treat hypoadrenocorticism before the thyroid gland is clarified. In the majority of dogs with hypoadrenocorticism, cTSH normalises a few weeks after glucocorticoid substitution, but in rare cases it may take 3-4 months.

What role do thyroid autoantibodies (TgAA) play when diagnosing hypothyroidism in dogs? add

The detection of thyroglobulin autoantibodies (TgAA) is indicative of lymphocytic thyroiditis and is positive in about 50% of dogs with hypothyroidism.

A possible explanation for the lack of antibodies in hypothyroid dogs is a different aetiology, i.e. if there is atrophy instead of inflammation.

Conversely, the antibodies can also be detected in euthyroid dogs. Follow-up studies have shown that approximately 15% of euthyroid TgAA-positive dogs become antibody-negative again without developing hypothyroidism. A similar proportion develops hypothyroidism within about 12-18 months, while the other antibodies remain positive without becoming hypothyroid

A determination of the autoantibodies does not serve to confirm hypothyroidism. Their detection does not allow a statement about the thyroid function, but only gives an indication of the presence of lymphocytic inflammation.

I am used to undertaking stimulation / suppression testing to determine the presence of endocrine disease – do these exist for dogs with suspect hypothyroidism? add

Both the TSH stimulation test and TRH stimulation tests have been studied as diagnostic methods for canine hypothyroidism.

The TSH stimulation test checks the reserve capacity of the thyroid gland. First a basal T4 value is gained, then a dosage of TSH preparation is administered and a second T4 value recorded after 6 hours. It is considered as the gold standard method for diagnosis of this condition.

However, the test is performed with recombinant human TSH (rhTSH; Thyrogen) which is expensive and hard to locate. It is for this reason that practically, few TSHSTs are undertaken.

The TRH stimulation test is not recommended, as even euthyroid dogs cannot show an increase in T4 after stimulation.

Could diagnostic imaging help in suspected cases of canine hypothyroidism? add

Ultrasound, CT, MRI and scintigraphy may all add useful information to your diagnostic picture. However often the cost, availability or need for experienced interpretation can exclude these as diagnostic tolls for the primary care veterinarian.

What other factors can influence thyroid hormone concentrations in dogs?

Non-thyroid diseases and certain medications, such as cortisone, can lead to a decrease in thyroid hormones and simulate hypothyroidism.

Veterinary professionals can find out more information on this topic by logging into our dedicated webpage.

How is canine hypothyroidism treated?

If the laboratory results confirm the diagnosis of hypothyroidism, then medical treatment is relatively straightforward. Levothyroxine sodium is the medication of choice.

Levothyroxine is a synthetic replacement for the body's thyroid hormone T4. Medication is usually given orally on a daily basis and must be given for the duration of the dog’s life. Dog’s will require regular monitoring appointments including blood samples to determine the correct dose and regimen.

What is the prognosis for dogs diagnosed with canine hypothyroidism?

The prognosis with lifelong medical treatment is good. Improvements are usually seen really quickly after commencing therapy. An increase in energy levels, improvements in biochemical parameters and eventual hair regrowth can all be expected. Dechra provide treatment solutions for patients with canine hypothyroidism. For further information on how Dechra can support veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses with the treatment of this important condition, log-in to the dedicated webpage.

Alternatively, to put this information into practice Dechra’s dedicated training portal, the Dechra Academy, gives veterinary professionals free access to a number of educational topics, facilitating learning at any time or place that suits. The canine hypothyroidism course contains case examples to put the knowledge from this article to the test.

Summary of key points

- Canine hypothyroidism is a commonly diagnosed endocrine condition in dogs.

- For the majority of dogs, the condition occurs as a result of either immune mediated destruction of the thyroid glands or due to idiopathic thyroid atrophy.

- As more than 75% of thyroid tissue must be destroyed before clinical symptoms present themselves, the onset of disease is usually insidious.

- Clinical symptoms of canine hypothyroidism are hugely variable, however those impacting on metabolism (e.g. lethargy and weight gain) and the skin (e.g. alopecia and secondary infection) are most commonly reported.

- Diagnosis is made using a combination of clinical signs displayed and the findings from specific endocrine tests.

- Aside from iatrogenic cases, there are no methods of prevention for canine hypothyroidism.

- Prognosis is good with appropriate lifelong medical treatment, primarily with levothyroxine sodium.

Additional resources

The Dechra Academy

Helping you as a veterinary professional to upskill and keep up-to-date with the latest thinking through completely free, modern learning experiences.

Put your learning to the test by logging-on and completing our course on canine hypothyroidism today!

SPECIFIC Endocrine Support

SPECIFIC diets have been developed by veterinary healthcare professionals and are made with high levels of omega-3 to provide optimum nutrition for the individual need

– including endocrine disease.

Canine Cushing’s Syndrome

Canine Cushing’s syndrome is the term used for a range of clinical syndromes displayed in the dog, caused by a chronic excess of glucocorticoid activity.

Authors

Emily Armstrong BVSc MRCVS

Veterinary Technical Manager

Dechra Veterinary Products

Isabelle Walliser Dr. med. vet.

Product Manager (Endocrinology)

Dechra Veterinary Products

References add

-

Graham PA , Refsal KR & Nachreiner RF. (2007) Etiopathologic findings of canine hypothyroidism. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 37(4): 617–631

-

Mooney CT & Shiel RE. (2012) Canine hypothyroidism. In: Mooney CT , Peterson ME , Editors. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Endocrinology. Fourth edition. BSAVA Gloucester 63–91

-

Tappin S. (2015) How to diagnose canine hypothyroidism. BSAVA Companion 10:16-2