Hypoadrenocorticism can be classified as either primary or secondary.

The primary form of the condition, otherwise known as Addison’s disease, occurs as a result of destruction of the adrenocortical tissue itself. In most cases, this destruction appears to be immune mediated in origin. Rarer causes of destruction of the adrenal cortex include drug therapy with mitotane or trilostane, creating disease purposefully in order to treat another condition (i.e. by performing a bilateral adrenalectomy) and infectious / infiltrative disease.

Secondary hypoadrenocorticism occurs due to suppression of stimulatory hormone. Therefore, there is a deficiency in glucocorticoid due to a lack of production of ACTH. This can occur naturally, after surgery or can occur due to abrupt cessation of pharmaceuticals with glucocorticoid action. More uncommonly, there can be state of secondary mineralocorticoid deficiency due to a lack of renin.

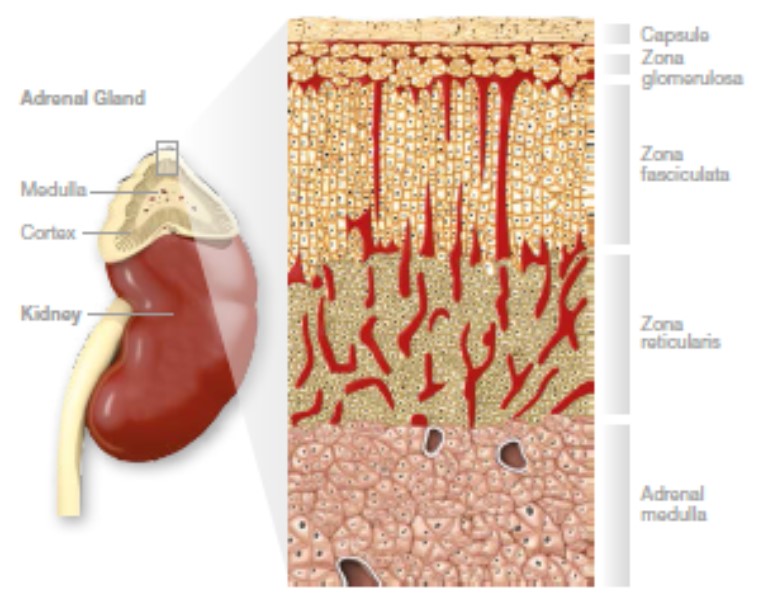

The adrenal gland itself is split into a cortex and a medulla. The cortex compromises approximately 75% of the adrenal gland itself and more specifically is split into three regions: the innermost is the zona reticularis; next is the zona fasciculata; and the outer region is termed the zona glomerulosa (Figure 1). It is these three zones that are responsible for producing a range of steroid hormones.

Figure 1- Diagram showing the architecture of the adrenal gland

Physiology of the Adrenal Glands

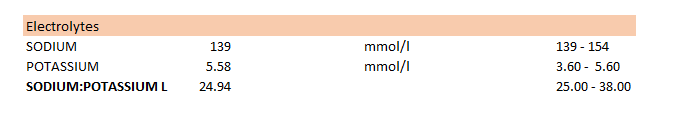

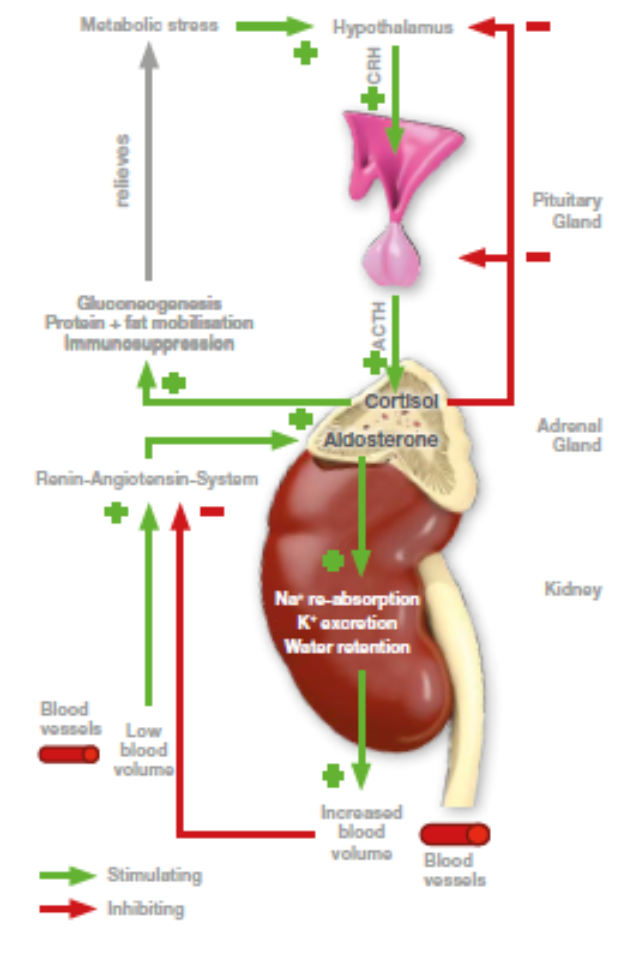

Aldosterone is the principle mineralocorticoid hormone and is produced by the zona glomerulosa. Its release is, in part, regulated by the renin-angiotensin system (Figure 2) and its major function is to control blood volumes by the regulation of body electrolytes. Dogs with a deficiency in aldosterone have low sodium and/or increased potassium levels alongside low blood volume. Clinically, this can manifest as dehydration, gastrointestinal signs, bradycardia and muscle weakness.

Cortisol is the main glucocorticoid hormone secreted by the zona reticularis and fasciculata. Its release is under the control of ACTH secreted from the anterior pituitary, which in turn is controlled by CRH release from the hypothalamus (Figure 2).

Cortisol can be thought of as the hormone which protects the body against the long term effects of stress. Clinically, a deficiency in cortisol leads to weight loss, lack of appetite, anaemia and low blood sugar levels.

Figure 2 - Diagram depicting the regulation of Aldosterone and Cortisol